Obesity and Women's Health

Abstract

Obesity negatively impacts the health of women in many ways. Being overweight or obese increases the relative risk of diabetes and coronary artery disease in women. Women who are obese have a higher risk of low back pain and knee osteoarthritis. Obesity negatively affects both contraception and fertility as well. Maternal obesity is linked with higher rates of cesarean section as well as higher rates of high-risk obstetrical conditions such as diabetes and hypertension. Pregnancy outcomes are negatively affected by maternal obesity (increased risk of neonatal mortality and malformations). Maternal obesity is associated with a decreased intention to breastfeed, decreased initiation of breastfeeding, and decreased duration of breastfeeding. There seems to be an association between obesity and depression in women, though cultural factors may influence this association. Obese women are at higher risk for multiple cancers, including endometrial cancer, cervical cancer, breast cancer, and perhaps ovarian cancer.

The prevalence of obesity is rising. The World Health Organization estimates that more than 1 billion people are overweight, with 300 million meeting the criteria for obesity.Twenty-six percent of nonpregnant women ages 20 to 39 are overweight and 29% are obese. This article will review the wide-ranging effects that obesity has on both reproductive health and chronic medical conditions in women.

A PubMed search was performed using the key words “obesity,” “overweight,” “body mass index” (BMI), “gender,” “women's health,” and the condition reviewed. The most recent evidence-based articles were included in the review. The evidence level of each article was determined by the authors based on the type of study, randomization, the number of participants, and loss to follow-up.

Table 1 provides a classification for overweight and obesity based on BMI.Waist circumference can also be used to classify overweight and obesity. In women, a waist circumference of >35 inches (88 cm) is high risk, whereas in men the level is >40 inches (102 cm). Research varies in the measurements of obesity used to classify participants in each study.

Table 1.

Classification of Obesity Based on Body Mass Index (BMI)3

| Classification | BMI |

|---|---|

| Underweight | <18.5 |

| Normal Weight | 18.5–24.9 |

| Overweight | 25.0–29.9 |

| Obese | |

| Class I | 30.0–34.9 |

| Class II | 35–39.9 |

| Class III* | >40 |

- * Morbid obesity or extreme obesity.

Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

The risk of diabetes mellitus (DM) increases with the degree and duration of being overweight or obese and with a more central or visceral distribution of body fat. Increased visceral fat enhances the degree of insulin resistance associated with obesity.4 In turn, insulin resistance and increased visceral fat are the hallmarks of metabolic syndrome, an assembly of risk factors for developing diabetes and cardiovascular disease.4–6

The Nurses’ Health Study followed 84,000 female nurses for 16 years and found that being overweight or obese was the single most important predictor of DM.7 An increased risk of DM was seen in women with BMI values >24 and a waist-to-hip ratio >0.76.8 After adjusting for age, family history of diabetes, smoking, exercise, and several dietary factors, the relative risk (RR) of DM for the 90th percentile (BMI = 29.9) versus the 10th percentile (BMI = 20.1) was 11.2 (95% CI, 7.9–15.9).5 A recent meta-analysis similarly found a pooled RR for developing DM of 12.41 (95% CI, 9.03–17.06) among obese women.9

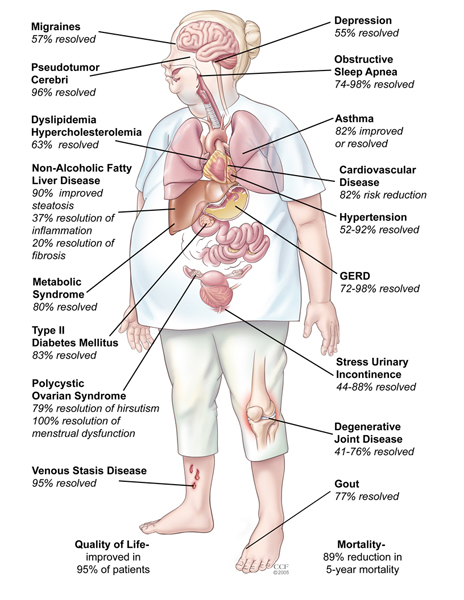

In morbidly obese patients (BMI >40 or >35 with major comorbidities), weight loss surgery can be considered if conservative measures fail.5 In one Swedish study, 68% of obese patients with DM who underwent gastric bypass surgery and subsequently lost weight went into remission.4 A systematic review that included more than 135,000 patients (80% women) found that bariatric surgery resulted in complete resolution of diabetes in 78% of patients and improvement in diabetic control in more than 86% of patients.10 These patients had improvements in insulin levels, fasting glucose levels, and glycosylated hemoglobin levels.10

Obesity and Coronary Artery Disease

Obesity is an independent risk factor for the development of coronary artery disease (CAD) in women and is an important modifiable risk factor for prevention of CAD.11 The mechanism of action is likely the relationship between obesity and insulin resistance. In a large cohort study of 37,000 women in Washington state, women with a BMI ≥35 had an odds ratio (OR) of 2.7 for CAD and an OR of 5.4 for hypertension.12

Abdominal obesity may be more harmful in women than BMI or weight alone. Waist circumference is an independent risk factor for developing CAD in both normal-weight women and overweight women.11 The Interheart global case-control study of 6787 women from 52 countries found that abdominal obesity was more predictive of myocardial infarction than was BMI alone.13 A prospective cohort study of more than 44,000 women in the Nurses Health Study found an association between having a waist circumference of >88 cm and the risk of cardiovascular mortality. Women with a waist circumference of >88 cm had a RR of death from cardiovascular disease of 3.02 (95% CI, 1.31–6.99).8 Waist-to-hip ratio is another significant predictor of death from cardiovascular disease, with a RR of 3.45 (95% CI, 2.02 to 6.92) in women with a ratio of >0.88.14

A meta-analysis that included data on more than 22,000 patients (72% women) looking at the relationship between bariatric surgery and cardiovascular risk factors found that hyperlipidemia improved in 70% of patients after surgery and hypertension was resolved in 62% and improved in 78%.15

Previous SectionNext Section

Obesity and Musculoskeletal Pain

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention statistics show that more than 31% of obese adults reported a doctor diagnosis of arthritis compared with only 16% of non obese adults.16 Obesity has been implicated in the development or progression of low back pain and knee osteoarthritis (OA) in women.

The mechanism by which obesity causes lumbar back pain is poorly understood, but the contribution of both mechanical and system factors is likely.17 Direct mechanical stress on the intervertebral discs and the indirect effects of atherosclerosis on blood flow to the lumbar spine are suspected to be mechanisms through which obesity affects the discs, leading to subsequent low back pain. Further research to elucidate the exact mechanism is needed.18

Obesity at age 23 increases the risk of low back pain onset for women within 10 years19(Table 2). The increased burden of obesity is more obvious as women age, with significantly more obese women over the age of 40 reporting low back pain and lumbosacral radicular symptoms.23 These symptoms increase further in obese women over the age of 54.24 This data supports the theory that obesity over time contributes to low back pain and that weight loss may help prevent the onset of low back pain in obese women. There is no evidence to support the recommendation of weight loss to treat low back pain once the pain is present.

Table 2.

Effects of Obesity on Low Back Pain (LBP)

| Authors | Assessment of Obesity | Results | Effect*(OR [RR]) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brown et al (20) | BMI >30 | Increased incidence of LBP | 1.26 (1.08–1.48) |

| Shiri et al (21) | BMI >35 in women aged 24–39 years | Increased incidence of LBP | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) |

| Tsuritani et al (22) | BMI >24 vs BMI = 20–24 in women >40 years old | Increased incidence of LBP and disability | 1.46 (0.78–2.47)† |

| 1.29 (0.74–2.25)‡ | |||

| BMI >26 vs BMI = 20–24 in women >40 years old | Increased incidence of LBP and disability | 1.22 (0.58–2.57)† | |

| 2.44 (1.24–4.81)‡ | |||

| Guh et al (9) | BMI >30 | Increased incidence of chronic LBP | 2.81 (2.27–3.48) |

- * All odds ratios (OR) and relative risk (RR) are compared to women with body mass index (BMI) <25, unless otherwise noted.

- † Back pain.

- ‡ Disability.

The data supporting the link between obesity and knee OA in women is even more staggering. The factors underlying the association of obesity with knee OA have not been entirely elucidated. Obesity leads to an excess load on the joint, increased cartilage turnover, increased collagen type 2 degradation products, and increased risk of degenerative meniscal lesions. Although all of these have been theorized to lead to knee OA no causal relationships have been demonstrated to date.25,26

Studies have shown that women with a diagnosis of knee OA have an average BMI that is 24% higher than women without OA.27 For every 2 units of BMI gain, the risk of knee OA increases by 36%,28 and 1 category shift downward in BMI from obese to overweight may avoid 19% of new cases of severe knee pain29 (Table 3). The importance of prevention of knee OA is highlighted by the subsequent burden of surgery. An estimated 69% of knee replacements in middle-aged women in the United Kingdom have been attributable to obesity.33 Dietary weight loss in combination with exercise effectively led to significant improvements in pain and physical function in women with knee OA over 18 months in the Arthritis, Diet, and Activity Promotion Trial.34 A separate, randomized clinical trial evaluating rapid weight loss found that a 10% weight reduction improved function by 28%, with a number needed to treat of <4 patients (95% CI, 2–9 patients) to achieve a 50% improvement in the WOMAC score, which is a measure of joint pain, stiffness, and function.35

Table 3.

Effects of Obesity on Knee Osteoarthritis

| Authors | Assessment of Obesity | Results | Effect*(OR [RR]) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abbate et al (30) | BMI: heaviest quartile vs lowest quartile | Increased diagnosis of knee OA | 5.27 (3.05–9.13) |

| Weight: heaviest quartile vs lowest quartile | Increased diagnosis of knee OA | 5.28 (3.05–9.16) | |

| Grotle et al (31) | BMI >30 | Increased diagnosis of new knee OA within 10 years | 2.81 (1.32–5.96) |

| Holmberg et al (32) | BMI increase from 23 to 25 | Increased radiograph diagnosis of knee OA | 1.6 (0.9–3.1) |

| Liu et al (33) | BMI >30 vs BMI <22.5 | Increased rates of knee replacement | 10.51 (7.85–14.08) |

| Patterson et al (12) | BMI >35 | Increased rates of knee replacement | 11.7 |

- * All odds ratio (OR) and relative risk (RR) are compared to women with body mass index (BMI) <25, unless otherwise noted.

- OA, osteoarthritis.

Obesity and Infertility (Including Polycystic Ovary Syndrome)

Obesity affects fertility throughout a woman's life. The impact of obesity and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) on reproductive function can be attributed to multiple endocrine mechanisms. Abdominal obesity is associated with an increase in circulating insulin levels. This results in increased functional androgen levels (caused by suppression of sex hormone–binding globulin synthesis and increased ovarian androgen production). Chronic elevation of circulating estrogen is caused by aromatization in peripheral adipose tissue. The resulting hyperandrogenism and menstrual cycle abnormalities are clinically manifested in part by anovulatory cycles and subfertility. Additionally, leptin inhibits ovarian follicular development and steroidogenesis and thus may contribute to reproduction difficulties in obese women.36

The impact of obesity on reproduction starts at a young age. Obese girls frequently experience the onset of puberty at a younger age than their normal-weight peers.37Between the late 1960s and 1990, during a time of increasing prevalence of childhood obesity, the median age of menarche decreased by approximately 3 months in white girls and 5.5 months in black girls in the United States.37

Obesity negatively affects contraception. Older studies have shown that hormonal contraception methods are less effective in obese women.37 For example, a retrospective cohort analysis of 2822 person-years of oral contraceptive use suggested that women in the highest quartile of body weight (≥70.5 kg) had a 60% higher risk of failure than women of lower weight. This study also found that the increased risk of failure associated with weight was higher for women using very low-dose or low-dose oral contraceptives.38 However, a recent large cohort study in Europe did not show a difference in contraceptive efficacy of oral contraceptive pills based on BMI.39

A multicenter study of 1672 healthy, ovulating, sexually active women randomized to receive the transdermal patch Ortho-Evra (Ortho-McNeil-Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Raritan, NJ) for 6 or 13 cycles found a higher rate of failure (pregnancy) in women weighing >90 kg (RR 58; 95% CI, 10.8–310).38 Additionally, a study of 1005 women using the levonorgestrol vaginal ring demonstrated higher rates of pregnancy at 1 year for heavier patients (1.7% for a 40-kg woman; 9.8% for an 80-kg woman).37 Obesity is a risk factor for technical failure of tubal ligation surgery (OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.2–2.6).40The intrauterine device may be one of the few reliable contraception options whose efficacy does not seem to be affected by BMI.37 Product inserts rarely comment on weight-specific guidelines (Table 4).

Table 4.

Manufacturer's Labeling: Weight-Based Precautions for Hormonal Contraception

| Contraceptive | Precautions |

|---|---|

| Triphasic oral contraceptive (eg, Ortho Tri Cyclen, Ortho-McNeil-Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Raritan, NJ) | Increased body weight and surface area are associated with decreased hormone concentration (overweight is not listed as a precaution). |

| Monophasic Oral Contraceptive (eg, Loestrin 24 Fe, Warner Chilcott, Rockaway, NJ) | No weight-specific comments. |

| Progesterone-only contraceptive (eg, Ortho Micronor, Ortho-McNeil-Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Raritan, NJ) | No weight-specific comments. |

| Transdermal contraceptive (eg, Ortho Evra, Ortho-McNeil-Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Raritan, NJ) | Consider decreased effectiveness >90 kg (this is listed as a precaution). |

| Intravaginal ring (eg, Nuva ring, Schering-Plough Corp., Kenilworth, NJ) | No weight-specific comments. |

| Implantable progesterone (eg, Implanon, Schering-Plough Corp., Kenilworth, NJ) | Effectiveness not defined because women with >130% of ideal body weight were not studied. However, the hormonal concentration is inversely related to body weight and thus may be less effective in overweight patients. |

| Injectable progesterone (eg, Depo-provera, Pfizer, Inc., New York, NY) | No weight-specific comments. |

| Hormonal intrauterine device (eg, Mirena, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Montville, NJ) | No weight-specific comments. |

Although most attention has focused on the impact of obesity on ovulation, other studies suggest a multifactorial impact. A recent national survey in France found that obese women were less likely to access contraceptive health care services and had more unplanned pregnancies.42 The US National Longitudinal Survey of Youth prospectively examined the association between body weight in young adulthood and achieved fertility in later life.43 Obese young women and men were less likely to have their first child by the age of 47 than were their normal-weight counterparts (for women: RR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.61–0.78; for men: RR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.66–0.84). This association was partly explained by a lower probability of marriage among obese patients, suggesting both a social and biologic effect on reproductive behavior.43

A retrospective cohort study of 22,840 women demonstrated that obesity was associated with reduced fecundity for all weight-adjusted groups of women and persisted for women with regular cycles.44 In addition, obesity may alter the quality of oocytes and embryos.45 Some studies demonstrate increased female sexual dysfunction in obese patients, whether caused by the physical or psychological impacts of obesity on female sexuality.36

Obesity is frequently associated with disturbances in the menstrual cycle. Cross-sectional studies indicate that 30% to 47% of overweight and obese women have irregular menses.46 PCOS frequently causes menstrual irregularity and is very common among obese women, though the actual prevalence is unclear. Although obesity may amplify the effects of PCOS, it is not a diagnostic criteria for PCOS. Approximately 20% of women with PCOS are not obese.47

Weight loss can improve the fertility of obese women by the return of spontaneous ovulation, thus leading to the recommendation of implementing weight-loss interventions (diet, exercise, medication treatment) as initial management of infertile overweight and obese women.48

A systematic review49 assessing pregnancy and fertility after bariatric surgery reported that although the available data are not optimal, surgery may have a beneficial influence on fertility. This is supported by the normalization of hormones in PCOS and the correction of abnormal menstrual cycles after surgery.

Obesity and Pregnancy

An Australian study of more than 14,000 pregnant women found that 34% were overweight, obese, or morbidly obese.50 In a US study of 9 states that included more than 66,000 women, there was a 22% rate of obesity among pregnant women in 2002 to 2003, which was up 69% since 1993.51 The subgroups of women with the highest increases in obesity rates were women aged 20 to 29 years, were African American, who had ≥3 children, and who were enrolled in the US Department of Agriculture's Women, Infants, and Children program.51 Obesity causes pregnancy complications because of elevated risks of antepartum complications and mechanical difficulties with delivery.

Obesity during pregnancy is related to higher overall health care expenditures, measured by length of stay after delivery and use of other services. The majority of this difference is caused by higher cesarean section rates and higher rates of high-risk obstetric conditions such as diabetes and hypertension. The mean length of stay after delivery was directly correlated to BMI52 (3.6-day stay for women with a normal BMI vs 4.4-day stay for women with a BMI >40.0).

Prepregnancy obesity contributes to the development of many pregnancy complications including pregnancy-induced hypertension, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, c-section, and neonatal death (Table 5). Compounding this finding is the fact that performing a cesarean section is more difficult in obese women.

Table 5.

Effects of obesity on pregnancy outcomes

| Condition | Type of Study | Effect* |

|---|---|---|

| GDM (53) | Meta-analysis | OR, 2.14 (1.82–2.53)† |

| OR, 3.56 (3.05–4.21)‡ | ||

| OR, 8.56 (5.07–16.04)§ | ||

| PIH (54) | Meta-analysis | OR, 2.5 (2.1–3.0)‡ |

| OR, 3.2 (2.6–4.0)§ | ||

| C-section (55) | Population-based cohort study | RR, 2.6 (2.04–2.51)‡ |

| RR, 3.38 (2.49–4.57) | ||

| Pre-eclampsia (53) | Meta-analysis | OR, 1.6 (1.1–2.25)‡ |

| OR, 3.3 (2.4–4.5)§ | ||

| Preeclampsia (56) | Retrospective cohort study | OR, 7.2 (4.7–11.2)§ |

| Induction of labor (56) | Retrospective cohort study | OR, 1.8 (1.3–2.5)§ |

| Postpartum hemorrhage (56) | Population-based cohort study | OR, 1.5 (1.3–1.7)‖ |

| Preterm delivery (<33 weeks) (56) | Population-based cohort study | OR, 2.0 (1.3–2.9)‖ |

| Stillbirth (57) | Systematic review and meta-anaylsis | OR, 1.47† |

| RR, 2.07‖ | ||

| Stillbirth (58) | Population-based cohort study | OR, 2.8 (1.5–5.3)‖ |

| Neonatal death (58) | Population-based cohort study | OR, 2.6 (1.2–5.8)‖ |

- * All odds ratio (OR) and relative risk (RR) are compared to normal weight pregnant women (body mass index [BMI] 18–25). Values in parentheses indicate 95% CI.

- † BMI 25–30.

- ‡ BMI 30–35.

- § BMI >35.

- ‖ BMI >30. GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus. PIH, pregnancy-induced hypertension.

Rates of fetal anomalies are increased in obese mothers as well, including neural tube defects (OR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.62–2.15), spina bifida (OR, 2.24; 95% CI, 1.86–2.69), cardiovascular anomalies (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.12–1.51), and cleft lip and palate (OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.03–1.40).61 However, maternal obesity was protective for gastroschesis (OR, 0.17; 95% CI, 0.10–0.30).61

Weight loss via bariatric surgery s to decrease many pregnancy complications. A retrospective cohort study that included 585 women who had undergone bariatric surgery found that women who had delivered children after surgery (as compared with women who delivered before surgery) had decreased rates of hypertension during pregnancy (OR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.20–0.74) and preeclampsia (OR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.09–0.44).62 Another study compared women who delivered before surgery to women who delivered after surgery and found decreased rates of diabetes (17.3% vs 11%; P = .009), hypertensive disorders (23.6% vs 11.2%; P < .001), and fetal macrosomia (7.6% vs 3.2%; P = .004).63

Obesity and Breastfeeding

Maternal obesity is associated with a decreased intention to breastfeed, decreased initiation of breastfeeding, and decreased duration of breastfeeding.64 Some of these effects may be cultural, having to do with one's body image, or physiologic caused by metabolic and hormonal effects of adipose tissue (ie, decreased milk supply). However, obesity may also be related to some confounders such as more pregnancy complications, which also have negative effects on breastfeeding rates.

A large study in the United Kingdom asked approximately 11,000 women at 32 weeks’ gestation about their level of concern regarding their shape and weight. After adjusting for multiple variables, those with “marked concern” for both were significantly less likely to intend to breastfeed.65 Another smaller study done in the United States among 114 women found that obese women intended to breastfeed for a significantly shorter period of time than other women.66

Several studies have demonstrated decreased breastfeeding initiation rates among obese women compared with normal-weight women.64,67–70 One chart review of 1109 white mother-baby dyads found that the overweight and obese mothers were more likely to quit breastfeeding at the time of discharge from the hospital compared with mothers who were normal weight (12.2% vs 4.3%).67

Obese women are at greater risk of a delay in milk production, which may be related to decreased rates of breastfeeding initiation. One study found that obese women had lower prolactin responses to suckling in the first week compared with normal-weight women.71 There is also evidence that excess body fat may impair mammary gland development before conception and during pregnancy by hormonal and metabolic effects.72

Maternal obesity is also associated with a shortened duration of breastfeeding.64,69,70,73,74 A Danish study of nearly 38,000 women observed that the greater the prepregnant BMI, the earlier the termination of breastfeeding.73 There is no data looking at future breastfeeding rates with subsequent pregnancies after weight loss.

Obesity and Depression

Population-based studies looking at the association between obesity and depression have yielded inconsistent results, with only some finding an association.75–78 The difference between sexes is similarly inconsistent. Some studies found an association between obesity and higher rates of depression in women but not in men79,81; others reported inverse associations between obesity and depression in both women and men.81

Most recently, data from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1988–1994) showed that obesity was associated with past-month depression in women (OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.01–3.3) but not in men (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 0.56–5.37).82This relationship was stronger when obesity was stratified by severity. One 5-year prospective study following a cohort of 2298 persons from Alameda County, CA, showed that the obese were at increased risk of depression (prevalence: OR, 2.16; 95% CI, 1.47–3.19; incidence: OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.29–3.47) but there was no effect of sex on this association.77

Although many social, psychological, and cultural factors likely contribute to the development of depression in obese women, one explanation argues that the stigma toward obese individuals in American society leads to low self-esteem and ultimately depression. Thus, in communities where a higher weight is acceptable, less psychological impact is observed. Another theory argues that obesity is not stressful per se, but the pressure to fit a norm and continued dieting leads to depression.83

Obesity and Cancer in Women

General

There is mounting evidence that obesity is a risk factor for developing gynecologic and breast cancers and that a higher BMI may also adversely impact survival. Obese women with cancer may have decreased survival because of later screening, comorbid illnesses, or poorer response to treatment. Obese women have increased surgical and possibly radiation complications. In addition, there is no current consensus regarding appropriate chemotherapy dosing for the obese patient.84 The increased levels of endogenous estrogen contribute to higher risk of several types of cancer.85,86

Endometrial Cancer

Endometrial carcinoma is strongly related to obesity. In premenopausal women, anovulation or oligoovulation that is associated with PCOS results in an endometrium that is chronically exposed to unopposed estradiol. This causes proliferation and the potential for neoplastic changes. Additionally, in premenopausal and postmenopausal obese women, increased insulin and androgens decrease the production of sex hormone–binding globulin. This leads to more and unregulated bioavailable estrogens in postmenopausal women.

In 2001 the International Agency for Research on Cancer found that there was convincing evidence based on large cohort and case-control studies that obesity is associated with a 2- to 3-fold risk in endometrial cancer.84,87 Epidemiologic data has found a 2- to 5-fold increased risk of developing endometrial carcinoma in premenopausal and postmenopausal women, and obesity has been associated with at least 40% of the incidence of endometrial cancer.86,88,89 Mortality from uterine cancer also seems to increase with BMI. A prospective study through the American Cancer Society following 495,477 women found that those with a BMI >40 had an endometrial cancer mortality increased RR of 6.25 (95% CI, 3.75–10.42.).85,90

Ovarian Cancer

The data linking ovarian cancer and obesity has been mixed.91–93 The rationale for an increased risk of ovarian cancer in obese women focuses on the hormonal impact of obesity. In 2001, the International Agency for Research on Cancer group found that the “evidence from the relatively few studies on body weight and ovarian cancer has been inconsistent and does not allow any conclusion to be drawn on a possible association.”87 If some subtypes of ovarian cancer are hormonally responsive, it seems logical to assume that unopposed estrogen could increase the risk of these cancers in obese women.84

Cervical Cancer

Several studies have shown both increased incidence and mortality from cervical cancer among obese women. This relationship may be because of decreased screening compliance among obese women.84 Obesity likely plays a more prominent role in the development of cervical adenocarcinoma than squamous cell carcinoma secondary to the role of additional estrogenic hormones.94 Disparities in cervical cancer screening by body weight persist for women who are severely obese. Obese white women may put off cervical cancer screening because of embarrassment or discomfort. Physicians recommend Papanicolaou smears for obese women at the same rate as for normal weight women.95,96

Breast Cancer

There is a well-established link between obesity and postmenopausal breast cancer.97It is hypothesized that this is because of an increase in the serum concentration of bioavailable estradiol.98 In 1997, a meta-analysis analyzed 51 studies, including 52,705 women with breast cancer and 108,411 women without breast cancer, and found that the strength of the estrogenic risk attenuated by obesity is stronger than with hormone replacement therapy. In fact, hormone replacement therapy does not increase the risk of breast cancer in obese, postmenopausal women (RR, 1.02 for BMI >25 kg/m2), though it is a significant risk for breast cancer in normal-weight women (RR, 1.73).99,100

Several meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and large cohort studies have shown obesity worsens breast cancer mortality. Obese women also have greater disease morbidity, including a higher recurrence rate, increased contralateral breast cancer, wound complications after breast surgery, and lymphedema.101 Poorer outcomes associated with breast cancer may be related to more aggressive disease at diagnosis, a higher likelihood of treatment failure, and a higher likelihood of delayed detection. Morbidly obese women are significantly less likely to report recent mammography. This is particularly true for white women.102,103 Obesity may also promote more rapid growth of metastatic disease because of impaired cellular immunity. In addition, the hyperinsulinemia found in some obese women may promote mammary carcinogenesis by increasing the levels of insulin-like growth factor and leptin, which have a synergistic effect with estrogen on mammary epithelial cells by promoting angiogenesis.101

Weight Loss and Cancer

Studies evaluating the long-term impact of weight loss on cancer risk among women have shown mixed results. In one large US study, cancer incidence and mortality data were compared between 6596 patients who had gastric bypass (between 1984 and 2002) and 9442 morbidly obese persons who had not had surgery. This study showed decreased overall cancer rates in women (P < .0004), with the strongest impact on endometrial cancer (P < .0001) and with less significant impacts on premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer (P < .54), cervical cancer (P < .78), and ovarian cancer (P < .19).104 A large Swedish study followed 13,123 obesity surgery patients and found no overall decrease in obesity-related cancers compared with the baseline incidence among obese individuals. No statistically significant trends were found for breast cancer (P < .60) or endometrial cancer (P < .83) over time. Therefore, efforts directed toward prevention of obesity might be more helpful than weight reduction in attempts to reduce the incidence of obesity-related cancer.105

Conclusion

Obesity is becoming more prevalent and has wide-ranging effects on a variety of women's health issues. Clinicians should counsel all women about the broad negative effects of obesity and the importance of controlling weight to prevent negative outcomes.

Ways to Lose Weight

1. Forget the Past and Future. A lot of progress is lost when thinking about all of the times you’ve tried to lose weight and failed, putting off dieting for a later date, or being stymied by all of the things you’ll have to do in the days to come. Focus on the now and get started!.

2. Don’t Sugar Coat Your Current State. Come to terms with how bad you’ve let yourself get, and make a promise never to return to where you’re at. It’s OK to be unhappy about the way you look, as long as you channel that energy into positive changes.

3. Don’t Overeat. This seems like a no-brainer, but it’s one of the hardest habits to break, and one of the most detrimental things you can do to your body.

4. Take on a Weight Loss Challenge. 90 days is the length of most challenges these days, but you can also find 30 and 60 day ones as well. What a challenge does is gets you to go hard out for a finite amount of time, so you can wrap your head around it. Just be sure to have a plan for when the challenge is finished.

5. Don’t Target a Specific Area. Spot treating rarely works, and can be very demotivating. Focus on improving your entire body and you’ll see those troublesome areas get better over time.

6. Don’t Let Giant Food Corporations Weigh You Down. It’s unfortunate the kind of “foods” the big food companies try to sell us. They’re filled with all sorts of additives and chemicals to get us to eat more of it. Take a timeout on pre-packaged fare.

7. Take Mandatory Me Time. If you’re always providing for others you won’t have the time needed to focus on your weight loss and fitness goals. Be sure to schedule some alone time to collect your thoughts.

8. There’s No One Way to Lose Weight. Don’t pigeonhole yourself into thinking that there’s only one way you could possibly get the results you want. There are many roads that lead to the same path, it’s about choosing the one that works best for you.

9. Why Not Live Up to Your Full Potential? Larry Winget says that the human race is the only living thing in the universe that chooses not to live to its fullest potential. The fit and healthy you is possible, so why not go for it!

10. Integrate Your Different Life Spaces. If you find that you’re an angel while at home, and a devil at work when it comes to eating junk, or vice versa, try to connect your different personas so you’re not working against yourself.

11. Eat More Superfoods. Lost on healthy foods to add to your diet? Our list of 66 Super Foods will give you plenty of insight.

12. You Can’t Get It Wrong. Many dieters think they’ve got to get it just right in order to be successful. But trying and failing is better than not trying at all. Every step you take in the right direction is helping, and is better than a step in the wrong direction.

13. Turn Up the Love. Dieting can put you in a state of self-loathing and grumpiness if you let it, but this is actually detrimental to your overall well-being. Show some love for yourself and be grateful for what you have and your efforts will be more effective.

14. Avoid Toxic People. You’ll likely find that there are some people in your life that seem to bring you down, especially when they see you start to change for the better. It’s best to avoid them if at all possible, and re-evaluate your relationship with them.

15. Find a Step-by-Step Program. If you’re just venturing into the world of fitness, or are too busy to develop your own plan, find one where they lay it all out for you, and just connect the dots each day.

16. Try Kettlebells. Kettlebells can be a bit intimidating at first, but they’re so effective because they combine an aerobic routine and strength training into one. Take a class to get the right form down, and then you can go off on your own.

17. Hack Your Life. These days it’s possible to look up any problem you’re having on the road to weight loss and get a fast answer from someone that’s been there. Example: Having trouble peeling a hard boiled egg? Here’s a way to skip the peeling process:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PN2gYHJNT3Y

18. Stop Changing the Formula. A true fitness professional has dedicated themselves to getting other in excellent condition. Follow their advice and stop trying to add your own ideas or methods, or twisting it up from what works.

19. Go to Bed Early. You set up the next day by how well you sleep the night before. If you’re staying up late into the night you’re making it more likely that you’ll start the day off on the wrong foot. Plus your organs and systems need sleep in order to function at their best.

20. Wake Up Early. If you go to bed early enough, you can wake up early and still get your 8 hours. You’ll also be allowing your body to flush out toxins by emptying your bladder and evacuating your bowels at the optimal time of day.

21. Imitate Your Favorite Celebrity Chef. The more meals you cook for yourself the better. You’ll have more control of the ingredients you use, and appreciate your food more since you made it.

22. Take a Longer View. We all want to lose weight like yesterday, but it took awhile for you to get to this point, and it’s going to take some time to get yourself back to good. Be patient and keep the bigger picture in mind.

23. Switch up the Chocolate. Just because you’re dieting it doesn’t mean you have to give up the chocolate, if that’s your weakness. Just make sure that it’s dark chocolate, and that it’s in moderation.

24. Turn Off the TV. You’ll not only benefit by being more likely not to veg out on the couch, you’ll skip the ads for all the fast food, pizza, and chain restaurants.

25. Meditate and Use Visual Imagery. Rather than focusing on how hungry you are or on the things you’re giving up, spend time clearing your head and picturing yourself the way you want to be.

26. Get a Therapeutic Massage. It’s more than just calories in and out, it’s about feeling good and few things can get you there faster than a massage by a licensed and experienced physical therapist.

27. Stop with the Fizz. Cutting carbonated beverages can go a long way towards helping you reach your goal weight. They not only work to dehydrate you, but many contain caffeine, and even more contain High Fructose Corn Syrup which will really trip up your efforts.

28. Work the Core. This doesn’t mean doing endless crunches or spot treating the stomach. There are many variations of exercises you can do. The core muscles help with many movements throughout the day, and can help relieve pressure on the back.

29 Take a Pass on the Latest Craze. Once you step back from the merry-go-round of the latest trends you can see how silly they are. Choose a solid program to follow and stick with it.

30. Focus on Being Healthier All Around. Yes, the goal is to lose weight, but if you dig deeper you’ll see that feel better is the core of the motivation, and that involves improving the body’s many functions with a holistic approach to health and well-being.

31. Ready, Fire, Aim! Don’t sit around waiting for the perfect strategy to come by, just get started doing something. The interesting thing is that once you start down the road to weight loss, the answers you need will come to you effortlessly.

32. Get to a Happy Place with Your Parents. In his book Heal the Hurt That Sabotages Your Life Bill Ferguson explains that a lot of the struggle in life comes from feelings of unworthiness caused by a dysfunctional relationship with your parents. If you have emotional connections to food this is a good place to start.

33. Pick a Guru, Any Guru. The problem is that there are so many gurus out there, many saying the same things, and others saying everyone else has it wrong, that it can stall your start. Pick the one that resonates most with you and go with what they say, at least until you reach your target.

34. Go Organic Whenever Possible. A recent study tried to debunk organic foods but missed the point entirely. You don’t buy organic because they have more vitamins or minerals, you buy it for all it doesn’t contain, like pesticides, chemicals, and additives.

35. Make More Money. It seems odd that money is connected to weight loss, but many people find that they need to start buying new clothes, eating better food, and getting more active. That costs money, and a lack of it can inhibit your progress.

36. Swim. This is one exercise that gets the whole body involved, helps with circulation, burns calories, and leaves you feeling great if you do it right. Don’t know how to swim or need a refresher? Check out the Total Immersion Swimming techniques here

37. Buy a New Pair of Pants. Buy a pair of pants in the size you want to be. But be careful to use them as a motivating factor as you near your goal, and not a demotivator as you struggle to get into them.

38. Use Better Metrics. Overall weight loss shouldn’t be your main goal, because this includes muscle mass that you can end up losing on starvation diets. What you should really be checking is your Body Fat Percentage (BFP) and your Body Mass Index (BMI). Choose healthy levels for each and strive for those.

39. Learn to Chillax. One characteristic that many dieters seem to share is that they get antsy and feel like they should always be doing something, because it’s being lazy that made them fat. But you have to learn to take some time to just relax and let your mind and body rest, especially now when you are making so many changes.

40. Eat a Light Breakfast. Your digestive juices are just getting going in the morning, so don’t overdo it. Keep it light so you fuel your body without slogging yourself down. SEE: 45 Healthy Breakfasts

41. Eat a Substantial Lunch.This is when your digestive juices are at their strongest, so you should have your largest meal of the day at this time.

42. Eat a Light Dinner. Your body is starting to slow down at this time, and this includes your digestive power. Try to avoid a heavy meal and keep in mind that meats take a long time to digest, so are best avoided later in the day.

43. Use Sea Salt Instead of Regular Salt. All of the nasty stuff that industrial grade salt is blamed for is not true for sea salt. In fact sea salt can help the body absorb and utilize the water that you drink.

44. Stop Smoking. It’s typical to gain some weight when you stop smoking, so if you’re overweight and a smoker you should cut out the cigarettes first, and then work on losing the excess pounds. SEE: 10 Ways to Quit Smoking

45. Have More Sex. This is one way to burn more calories and have fun at the same time.

46. Cut Back or Cut Out Alcohol. Alcohol not only contains a lot of calories, it’s also toxic to the liver, and the liver has a big role to play on making sure your colon, heart, and other organs are working in proper order.

47. Decide If You’re Going to Have a Free Day. A lot of modern workout programs include a free day, where you’re authorized to eat what you’ve been craving, skip on the exercise and then get back to the program the next day. You’ll need to decide if this will work for you, or if you think it would be too hard to go back to the program after a day of cheating.

48. Get a Few Wins Under Your Belt. If you’re coming off a long string of dieting losses, try setting a few weight loss goals that you are pretty sure you can achieve. This will boost your confidence in your abilities, and allow you to go after bigger goals down the road.

49. Get a Makeover. Getting a new body involves getting a new hairstyle and some new clothes. Make it a total body makeover and honor the new you that’s emerging.

50. Go the Extra Mile. Not literally, unless you want to, but Napoleon Hill includes this as one of the things that separates winners from losers. Those that succeed are willing to do a little more than the rest of the masses, and that’s why they get the things that few people have.

39. Learn to Chillax. One characteristic that many dieters seem to share is that they get antsy and feel like they should always be doing something, because it’s being lazy that made them fat. But you have to learn to take some time to just relax and let your mind and body rest, especially now when you are making so many changes.

40. Eat a Light Breakfast. Your digestive juices are just getting going in the morning, so don’t overdo it. Keep it light so you fuel your body without slogging yourself down. SEE: 45 Healthy Breakfasts

41. Eat a Substantial Lunch.This is when your digestive juices are at their strongest, so you should have your largest meal of the day at this time.

42. Eat a Light Dinner. Your body is starting to slow down at this time, and this includes your digestive power. Try to avoid a heavy meal and keep in mind that meats take a long time to digest, so are best avoided later in the day.

43. Use Sea Salt Instead of Regular Salt. All of the nasty stuff that industrial grade salt is blamed for is not true for sea salt. In fact sea salt can help the body absorb and utilize the water that you drink.

44. Stop Smoking. It’s typical to gain some weight when you stop smoking, so if you’re overweight and a smoker you should cut out the cigarettes first, and then work on losing the excess pounds. SEE: 10 Ways to Quit Smoking

45. Have More Sex. This is one way to burn more calories and have fun at the same time.

46. Cut Back or Cut Out Alcohol. Alcohol not only contains a lot of calories, it’s also toxic to the liver, and the liver has a big role to play on making sure your colon, heart, and other organs are working in proper order.

47. Decide If You’re Going to Have a Free Day. A lot of modern workout programs include a free day, where you’re authorized to eat what you’ve been craving, skip on the exercise and then get back to the program the next day. You’ll need to decide if this will work for you, or if you think it would be too hard to go back to the program after a day of cheating.

48. Get a Few Wins Under Your Belt. If you’re coming off a long string of dieting losses, try setting a few weight loss goals that you are pretty sure you can achieve. This will boost your confidence in your abilities, and allow you to go after bigger goals down the road.

49. Get a Makeover. Getting a new body involves getting a new hairstyle and some new clothes. Make it a total body makeover and honor the new you that’s emerging.

About Weight Loss Surgery

Gastrointestinal surgery for obesity, also called weight loss surgery or bariatric surgery, alters the digestive process so as to achieve rapid weight loss.

The operations can be divided into three types:

- restrictive

- malabsorptive

- combined restrictive & malabsorptive

Restrictive weight loss surgeries limit food intake by creating a narrow passage from the upper part of the stomach into the larger lower part, reducing the amount of food the stomach can hold and slowing the passage of food through the stomach. Malabsorptive weight loss surgeries do not limit food intake, but instead exclude most of the small intestine from the digestive tract so fewer calories and nutrients are absorbed. Malabsorptive weight loss surgeries, also called intestinal bypasses, are no longer recommended because they result in severe nutritional deficiencies. Combined operations use stomach restriction and a partial bypass of the small intestine.

Benefits of Weight Loss Surgery

- High Blood Pressure can often be alleviated or eliminated by weight loss surgery

- High Blood Cholesterol in 80% of patients can be alleviated or eliminated and in as little as 2-3 months post-operatively.

- Heart Disease in obese individuals is certainly more likely to be experienced when compared to persons who are of average weight and adhere to a strict diet and exercise regimen. There is no hard and fast statistical data to definitively prove that weight loss surgery reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease, however, common sense would dictate that if we can significantly reduce many of the co-morbidities that we experienced as someone that is obese, we can likewise that our health may be much improved if not totally restored.

- Diabetes Mellitus can usually helped and based upon numerous studies of diabetes and the control of its complications, it is likely that the problems associated with diabetes will be arrested in their progression, when blood sugar is maintained at normal values.

- Abnormal Glucose Tolerance, or Borderline Diabetes is even more likely reversed by gastric bypass. Since this condition becomes diabetes in many cases, the operation can frequently prevent diabetes, as well.

- Asthma sufferers may find that they have fewer and less severe attacks, or sometimes none at all. When asthma is associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease, it is particularly benefited by gastric bypass.

- Sleep Apnea Syndrome sufferers can receive dramatic effects and many within a year or so of surgery find their symptoms were completely gone, and they had even stopped snoring completely!

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease can be greatly relieved of all symptoms within as little as a few days of surgery.

- Gallbladder Disease can be surgically handled at the time of the weight loss surgery if your doctor has cause to believe that gallstones are present.

- Stress Urinary Incontinence responds dramatically to weight loss, usually by becoming completely controlled. A person who is still troubled by incontinence can choose to have specific corrective surgery later, with much greater chance of a successful outcome, with a reduced body weight.

- Low Back Pain and Degenerative Disk Disease, and Degenerative Joint Disease can be considerably relieved with weight loss, and greater comfort may experienced even after as few as 25 lost pounds.

THANK YOU FOR GIVING US YOUR PRECIOUS TIME AND READING THIS ARTICLE.FEEL FREE TO EXPRESS YOURSELF IN COMMENTS.TELL US WHAT WILL YOU LIKE TO KNOW ABOUT.

ANY SUGGESTIONS,COMMENTS OR QUERIES KINDLY CONTACT US AT FOLLOWING E.MAIL

auroraforeveryone@gmail.com .

Previous SectionNext Section

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank You.